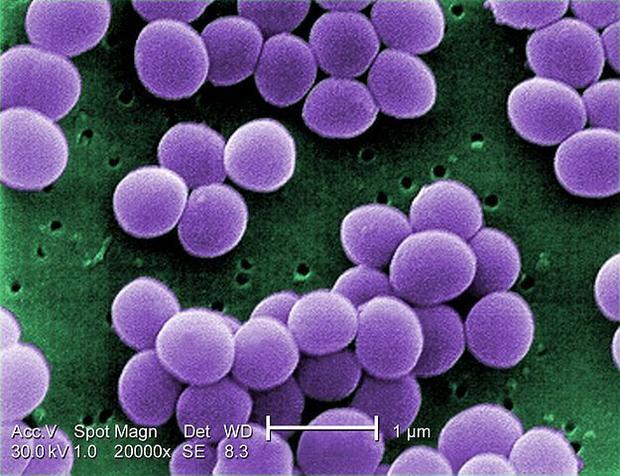

New research indicates that Staphylococcus bacteria can directly affect the neurons associated with the feelings of itchiness. What is of interest is why does this happen on some occasions and not others? The species of interest is S. aureus.

Staphylococcus species are very common members of the human skin microbiome. In terms of this, why do some people experience itchy sensations and not others? The answer may rest with the balance of the different microbial communities, where an ‘out of balance’ situation leads to those bacteria responsible for the itchy sensation moving into predominance.

Subsequent studies have shown how epicutaneous S. aureus exposure causes robust itch and scratch-induced damage.

Specifically, S. aureus can trigger a protein found on neurons that sends signals to the brain. This bacterium activates a biochemical pathway that leads us to want to scratch. When mice were exposed to these bacteria, they started to scratch, which got worse over several days. These mice also became very sensitive to stimuli that normally would not cause irritation or itch; these animals were itchy after only light touches, for example.

This appears to be the reason by S. aureus is found on almost every patient with the chronic condition atopic dermatitis.

Further study showed a bacterial enzyme called protease V8 is directly responsible for causing itch in mice. The V8 protease activates a protein called PAR1 on neurons that are found in the skin. These neurons carry sensory signals detected in the skin like touch, pain, and itch, to the brain.

PAR1 is usually inactive, but when it’s exposed to certain enzymes, including V8, ia portion of PAR1 is snipped off, activating the protein. This leads the brain to sense itch.

The researchers explored the hypothesis using a mouse model. This demonstrated that the activation of the PAR1 protein could be blocked by an anti-clotting medication. As a result, this drug halted itchiness.

The scientists are keen to assess if other microbes also trigger itch.

The research appears in the journal Cell. The paper is headed “S. aureus drives itch and scratch-induced skin damage through a V8 protease-PAR1 axis.”